FICKLE FRIENDSHIPS ON A STAGE

When is acting more than acting? When does true

performance merge into reality? When does suspension of disbelief transform

into belief – or for that matter into disbelief?

In Stanislavski’s famous ‘Method’, actors strive to

empathize with characters whom they portray – in order to ‘become’ a realistic

character; to give a sense that here, before you, is a ‘real’ person, a

character in living flesh.

The play ends – and the actor sheds her costume and her

character, comes back to reality and puts away pretense.

Or not. We act, we always act – we don our make-up,

dress for roles to meet the faces that we meet. We not think it false to play

the parts we play for each occasion – friend or lover, pupil, teacher,

passenger or parent, guard or engine driver, prince or pauper, chairman, child.

In J.D. Salingar’s ‘The

Catcher in the Rye’, the anti-hero Holden Caulfield finds the world

a ‘phony’ place, where everyone is acting parts, with only children undefiled.

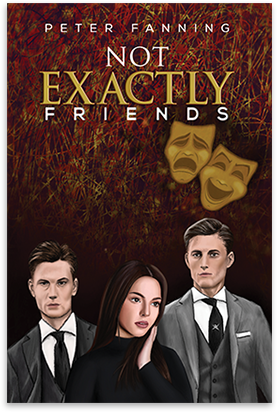

In the novel ‘Not

Exactly Friends’, the central character believes he has the

friendship of an older, wiser boy, offering protection in a world of callous

cruelty. He trusts him, just as children trust their siblings and their parents

– unless, that is, the circumstances change.

But then he starts to wonder if that friendship’s just

another role and that his friend and those around are simply playing

characters. The tale is focused on the stage. A series of performances, both on

and off, lead Charlie to suspect that friendship’s less than it appears.

Shakespeare writes that ‘All the world’s a stage – and all the men and women

merely players.’ Elsewhere, he declares that ‘Friendship is feigning and loving

mere folly.’

The setting is seductive summer, many years ago, where

Charlie’s acting in a play. He falls in love – or so he thinks. His memory

assures him that the girl he loves must love him too. But in this world of

memories and fools, perhaps we fool ourselves. We speak about ‘our truth’,

‘our’ memories – as if those memories were solid as reality. For Charlie is a

dreamer and his truth is true, as long as it does not collide with other

people’s truths and memories.

He plays his part, both on and off the stage, an actor

through and through, acting out the Schoolboy and the Lover and the Pantaloon;

trusting others, self-deceiving; trusted and deceived in turn; while Millie,

his hard-bitten friend and longstanding companion, ruefully observes ‘This is

the only world we’ve got.’

What price fake news, conspiracy and rumour? That way madness lies. This

is, indeed, the only world we’ve got

Post Views : 316